Columbine, Dave Cullen, and Gus Van Sant's Elephant

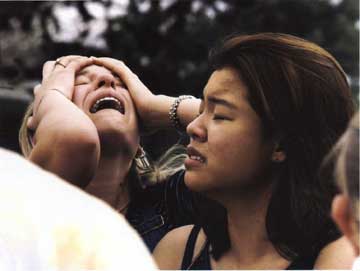

There were school shootings before and after Columbine, but few of them elicited such a sense of shock and questioning as the events of April 20, 1999. People watched the nightmare unfold live on the news: sobbing students, panicked parents, a wounded boy hanging out the second-story window. It was the first time the threat of school shootings--kids going on killing sprees--truly entered the public's awareness. How could something like this happen? Why did these boys do it?

I was in middle school when Columbine happened. It was the first major world event that I was old enough to be fully conscious of (unlike, say, the Oklahoma City bombing). I was still young enough, though, that the events of that day aren't as finely crystallized in my mind as those of September 11, two years later. Mostly I remember my teachers, upon hearing the news, looking grim and shaken. My teachers' and parents' reactions made as much of an impression on me as the actual events. Columbine was something we talked about for a long time. With each passing anniversary of the attack, I felt a jolt of surprise that so much time had passed--it seemed like it had just happened yesterday.

Our feelings and fears were raw. In our dismay, we tried to come up with answers, possible motives or causes of Eric Harris's and Dylan Klebold's actions. We needed a scapegoat. They were angry outcasts who target jocks and the popular kids. They were bullied misfits who finally snapped. They were part of the Trenchcoat Mafia; they were neo-Nazis, they listened to satanic music. Violent video games and Marilyn Manson made them do it. Their parents must have done something (or failed to do something) to make them that way.

In truth, almost none of this is true. In our nation's grief and anger, we grasped for some explanation, some way to make sense of everything. If there was some sure cause, something or someone we could blame--guns, parents, bullies, violent movies--then there might be a way to prevent other Columbines. The words Littleton, Eric and Dylan, especially Columbine entered our collective consciousness, came to mean something tragic, frightening. Eric and Dylan frightened us because we understood so little about them. What made them tick? There was so little to go by--their yearbook pictures showed seemingly normal, happy high school seniors. Then there was the iconic image captured by a security camera: two boys stalking through an abandoned cafeteria, guns held at the ready, like players in a video game.

Unfortunately, their classmates, still hysterical over the attack, were quick to tell reporters what they wanted to hear. Misinformation spread like wildfire, and the public gobbled it up.

Dave Cullen's Columbine

Ten years later, in 2009, Dave Cullen dispelled the rumors and false information, built up to almost mythic proportions, in his book titled, simply, Columbine. One of the original reporters on the scene, he culled through hundreds of witness accounts, police reports, interviews, and the killers' collection of journals and videos documenting the months they spent planning the massacre.

Eric and Dylan didn't snap. They were methodical, calm, making diagrams of the school's layout, amassing an arsenal of assault weapons and homemade pipe bombs. Cullen was able to get into the boys' heads through their journals, and the contents, previously unavailable to the public, are truly chilling.

Some of the truths unveiled in Cullen's book:

- Eric and Dylan were not bullied, nor outcasts. They both had jobs, a circle of friends. Dylan had a date to the prom three days before the planned attack.

- The police had records on both the boys prior to the shooting. They had been arrested earlier for breaking into a van to steal electronic equipment. They were ordered to complete a diversionary program and community service. The police also received multiple complaints from the Browns, whose son Brooks was the subject of death threats made on Eric's website. However, an affidavit for a search warrant to investigate Eric Harris was never filed.

- Eric showed signs of sociopathy: glibness, false charm, narcissism, lack of empathy and remorse. He was practiced at telling authorities--parents, teachers, cops--what they wanted to hear, and would brag about deceiving them in his journal. He wrote, "I hate the world," and recorded maniacal fantasies of killing as many people as possible.

- Dylan showed signs of depression and alcohol abuse. He wrote about wanting to end his life, but he lacked the drive to follow through on his own. He fell sway to Eric's determination to take down their classmates, Natural Born Killers-style.

- The killers had a lot more carnage planned for April 20. They planned to set off bombs in the cafeteria during its peak of activity. Beforehand, they even counted the stream of students entering the room to determine at which exact minute they could blow up the most people. The bombs would also collapse the ceiling, bringing down the library above it. Eric and Dylan planned to wait outside with their guns and pick off any survivors coming out the doors. They wanted to top the carnage of WACO and the Oklahoma City bombing. If not for faulty bomb equipment, an odd sign of carelessness, the death toll could have been in the hundreds.

- When the bombs failed, the boys improvised, shooting indiscriminately, wreaking the most havoc in the library. They didn't appear to have specific targets in mind--they killed in a spurt of twenty-three minutes, until they apparently grew bored, roamed the halls, and finally shot themselves, forty-five minutes into their killing spree.

- SWAT teams did not storm the building until an hour after the shooters had killed themselves. The cops instead formed a perimeter, having misread the situation as a hostage takeover. Since Columbine, police have implemented new procedures for active shooter incidents that call for immediate action.

Dave Cullen's book breaks the attack down to the minute, describing every step of the massacre. But he explores so much more than just the actual shootings. We get an in-depth look at the killers' backgrounds, their troubles in school, their months of careful planning, their actions on the days leading up to the attack.

We learn about the local police's cover-up of their mishandling the case. We hear from the witnesses, survivors, and the victims' families as they dealt with the aftermath (shock, grief, PTSD, healing). We discover how Columbine irrevocably altered the entire town, even years after the shooting. We get a glimpse, albeit small and guarded, of the boys' parents' reactions to their sons' actions.

Cullen gets inside the killers' heads in a way you'd never imagine possible and makes believable theories about what led these boys to mass murder. He speculates a bit about their feelings, motives, and thought processes, but he backs it all up with textual and video evidence. In this sense, his book follows in the footsteps of the landmark, oxymoronic nonfiction "novel"--Truman Capote's In Cold Blood.

Reading Columbine, it was like all the confusing information I had gathered over the years, like floating puzzle pieces, finally snapped into place in a clear picture. I felt like I finally understood the events of that day, finally had sense of who Eric and Dylan were. If I had trouble comprehending Columbine when I was just thirteen, I imagine it was just as difficult for the rest of the world.

Dave Cullen speaks about Columbine

Elephant

Gus Van Sant (the director of Good Will Hunting and Finding Forrester) directed the 2003 film Elephant in response to school shootings like Columbine. It takes place in a single day at a typical high school, following a handful of normal kids as they go about their mundane activities: football practice, class discussions, working in the photography lab or media center. If there's one way that this high school differs from any other I've seen, it's how rarely the kids are in actual class. Students seem to roam the halls at will, with little direction, no teachers present--some imagining of a public school wasteland by Van Sant?

A steadicam follows them as they wander through the halls. These long tracking shots, usually focusing on the back of the subject's head as he or she makes her way across campus, are the scenes that can lose viewers' interest. Long unbroken shots can be used for great dramatic effect (see Touch of Evil, The 400 Blows, Atonement, Children of Men for prime examples), but in Elephant they seem to be there just to drill into our heads that these characters' lives are completely unextraordinary. The realism of these scenes can either make us more reflective or completely frustrated.

There's nothing remarkable about any of the characters, either, which can make viewers bored with them or more sympathetic to their fates. There's John, a boy who has to deal with his father's alcoholism; Elias, a quiet kid who spends a lot of time with his photography; Michelle, the awkward girl who quietly listens to the girls making fun of her in the locker room (anyone who is awkward or shy can remember how painful these locker room experiences could be). These kids aren't really actors; much of their dialogue is improvised. There's a scene of three popular girls prattling on in the cafeteria, picking at their food, and then going into the restroom to purge together. If there's no real character development, it doesn't really matter. These kids aren't even characters, they're just real, ordinary people. Viewers will either identify with them more because they could be anyone, or they'll fail to connect with them at all, especially when their actions seem inexplicable.

What about the shooters? Much of the tension in the movie comes from the knowledge that there will be a school shooting, even though some would argue that nothing happens in the first 40 to 50 minutes of the film. Van Sant doesn't provide a reason or motive for the two boys who decide to go on a rampage. Alex, the quiet one, gets spitballs thrown at him in science class; the viewer can sense the deep depths of his anger when even playing Beethoven's Fur Elise on the piano cannot alleviate his frustration (he gives his sheet music the finger). Eric acts like the jokester, the boy in charge, playing shooting video games and teasing Alex's mom over a meal of pancakes mere hours before the shooting.

As much tension as there is building up in the film, the actual violence is mercifully brief. If you're hoping for bloody carnage and big explosions, you're in for a disappointment. Only a few of the killings occur on screen. The rest have to be imagined, which made the shooting scenes for me all the more chilling and uncomfortable to watch. You'll almost feel bad for expecting to see more deaths.

Elephant turns many of our expectations on their heads. There are no heroes, no police response, no teachers taking control of the situation. The principal cowers on the floor as Eric taunts him. One boy, Benny, strolls the halls, passing the raging fires and fleeing students in either a daze or a stupid form of bravado. His fate, after attempting to sneak up on Eric? He's shot point-blank.

The film most directly references Columbine. The duo of killers, the misapplied bombs, the massacre in the library, the halls filled with smoke and fire. The shooters even warn a boy away as they approach the school. Eric said to Brooks Brown moments before the attack: "Brooks, I like you now. Get out of here. Go home."

Van Sant offers no real answers, but he throws us a few hints, the way you'd tease a dog with a bone. Maybe Alex is mentally ill, the way he holds his ears against the rising tide of voices in the cafeteria, like he's in physical pain. Maybe he's been bullied, as evidenced by the spitball scene. Maybe the boys glorify Nazis--they watch a TV program on Hitler (but one of them can't even recognize him on screen). Perhaps violent video games, like the one Eric plays, desensitized them to violence. Maybe they are closet homosexuals, because Eric hops in the shower with Alex right before they go on their killing spree (Van Sant himself is homosexual). Maybe their parents were inattentive or neglectful; Alex's mom is kept faceless as she serves them breakfast. It could be they just wanted to kill--Alex reminds Eric to "have fun" as they go over their plans one final time. Van Sant gives us no concrete answers, because (at least back in 2003) we had no explanations for the Harrises and Klebolds of the world.

What can be done?

Is there anything that could have been done to prevent Columbine? Sadly, yes. The signs were there that Eric and Dylan were cooking up some trouble. People were just unable to read the signs correctly, in part because of Eric's gift of deceit. There's still no easy solution for Columbine. Sociopathy has no cure; it can't be treated by therapy. If Dylan had received some help before, he might not have gone along with Eric. We can never know how things may have gone differently.

The boys had a lot of hatred in their hearts. Some people are uncomfortable with the notion of evil. They look for some mental disease, some psychological or emotional defect that makes kids kill each other. But for a person with no conscience, no empathy for others' pain, I believe evil can slip into that empty place in the person's soul.

For more information

- Dave Cullen's official author site, including the NY Times bestseller COLUMBINE

Visit Dave Cullen's website for more details, Eric and Dylan's journals, and other documents